When my wife and I decided to have children, the plan was to produce one, undergo a two year “cooling off” period, have another and call it a career in the baby-making department. But nature had other ideas so our girls are five years apart.

At first this seemed like a better result than our original intent. At five years old my oldest had become “self sufficient,” a term many parents use if they don’t feel like actually playing with their kids if there is something good on ESPN.

Just put Disney Channel on in the other room and plop him down on the couch. He’s self sufficient.

In our case, “self sufficient” meant that the oldest could dress herself, use silverware, drink from a cup and generally get through the day without a 911 call, leaving us free to tend to the younger daughter’s every need.

But, as kids grow, you realize that siblings five years apart aren’t that much easier to please than children 55 years apart when it comes to providing activities that appeal to everybody. Nowhere is this more evident than when choosing a movie.

A few Fridays ago, my wife Sue was in the midst of her annual Vegas girlfriend trip. She has been going to Sin City at least once a year, sans me, since we’ve been married and I function quite well without her. But somehow word gets out that I’m home alone with the kids, causing relatives and neighbors I never knew existed to offer me dinner invitations, school pickups and activity drop offs. Sue is both amazed and exceedingly jealous when I casually mention that others have stepped up to assist me during her absence, as well she should be. I spend at least 50 nights a year away from home yet she is still awaiting the offer of a simple casserole.

So there we were one Friday, scanning the movie start times and trying to figure out what flick would appeal to a 13-year old soon-to-be eighth grader, her eight-year-old sister and their 47-year-old father. After rejecting Toy Story 3 (“we’ve already seen it”), Step Up 3 (“the first one was good but the second one was dumb”), and Cats and Dogs (“Dad, we don’t like cats”), we settled on Despicable Me. A quick check of the listings revealed that it was showing on two screens at the nearby multiplex.

Why two? Because one theatre was showing the movie in 3D. Not just 3D, mind you, but “EYE POPPING 3D,” the term being bantered around for seemingly every movie these days.

Naturally the start times for the “non eye popping 3D” version did not agree with the Schwem’s busy schedule. In other words, Dad couldn’t get dinner on the table fast enough. So we showed up at the multiplex a mere 10 minutes before the 3D version began. Immediately I noticed one thing about the movie that truly was eye popping: the price. Tickets for Despicable Me in 3D were $15 each as opposed to $9 for the regular and apparently boring version. Now I was out $45 and we hadn’t even reached the concession stand. An additional $20 later, we entered the theatre, dipped our now buttery hands into the barrel of used 3D glasses, and settled in.

First we had to endure the mandatory 25 minutes of “coming attractions.” Not surprisingly, five soon-to-be-released movies were promised in “eye popping 3D.” Most also starred “the voice of Tina Fey.” I made a mental note to start conserving funds in case my daughters wanted to attend any more movies in the next six months.

Eventually the attractions were over and Despicable Me began. With my glasses firmly, and uncomfortably, perched on my nose, I waited for the “eye popping” 3D effects that cost an extra six bucks per ticket.

I am still waiting.

Oh sure, at one point a Despicable Me character looked as if it was suspended right in front of me and I could reach out and squish its little animated head if the mood struck me. But that effect came and went in about ten seconds. For the remaining 89 minutes and 50 seconds of the movie, I saw absolutely nothing that merited cheap glasses and 15 bucks.

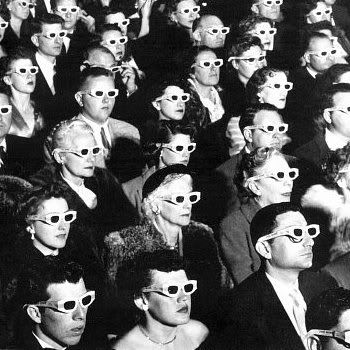

What exactly has changed about 3D movies since the 1950s? I pulled the accompanying photo off Google Images and it appears this audience had the same technology, except that the glasses were cardboard as opposed to plastic. The audience also had shorter hair and fewer tattoos than the moviegoers watching Despicable Me. But the technology itself? Heck, my mother, now in her mid-70s, told me stories of going to see 3D movies and literally jumping out of her seat at the effects.

I jumped from my seat exactly once during Despicable Me. It was just after I said to my kids, “Time to go.”

In 1974 I went to see Earthquake with some junior high school buddies. What lured us to the theatre was not the chance to see buildings falling over. It was the tagline that accompanied the ads: “In Sensurround.”

Nobody explained what Sensurround was. It was just supposed to make the earthquake experience more real to the moviegoer. In 2010, as our country continues to slog through a recession, I’m not sure I want movies to be more real. I’m looking forward to seeing Wall Street 2 this Fall but not if I’m going to come home and find my IRA has been mysteriously liquidated.

But in 1974 I sat in my seat and awaited the Sensurround effects. Less than 30 minutes into the movie, a “rat a tat tat” sound shook the theater at ear splitting decibels. It was if a machine gun battle was taking place in the theatre’s rear.

I DID jump from my seat and so did my buddies. Meanwhile, Charlton Heston barely escaped being buried under a toppling bridge.

Sensurround never really took off but isn’t it strange that, nearly 40 years later, I remembered that word and the effects it produced without having to consult either Wikipedia or Google?

Now I’m raising my kids in a world containing text messaging, mobile apps, on line everything and new technologies that truly are eye popping.

Yet it’s been a week since I saw Despicable Me and I’ve already forgotten what the movie was about. I certainly don’t remember any 3D effects.

Maybe “jaw dropping 4D” will be different.

One Against Three...and The Dog Makes Four is the blog of corporate stand-up comedian,author and nationally syndicated Tribune Media columnist Greg Schwem. Read how Greg survives in a family that includes his wife, two daughters and yes, a female dog. Hungry for more? Check out Greg's book, "Text Me If You're Breathing: Observations, Frustrations and Life Lessons From a Low Tech Dad" now available at your favorite on line or retail bookstore

Wednesday, August 25, 2010

Sunday, August 01, 2010

Like, what are you saying?

like

transitive verb

1 – to be suitable or agreeable to

2 – to feel attraction toward or take pleasure in

3 – every other word out of my daughter’s mouth

I love my kids. I truly do. I encourage communication with them. But despite the fact that they are my world and I heap affection on them at every moment, I hesitate to say that I “like” them. For, if I hear that word one more time, I’m like going to scream.

I am a stand-up comedian by trade. My profession relies on audience approval. Every time I walk on stage, I hope the audience will like me. But I don’t want them to “like, like me.”

Seriously, when did the word “like,” which has multiple meanings as evidenced by the above definitions taken directly from Merriam-Webster’s on-line dictionary, become the most overused and grating word in the English language?

Does anybody know? Perhaps I should ask country music superstar Carrie Underwood who, during a recent Today Show appearance, talked about like her marriage and like her upcoming tour and like her charity work and like the changes on American Idol. I have always liked Carrie Underwood, believing her music and her personality suitable for my kids. My oldest, now thirteen, even met her backstage before a concert and Carrie was exceptionally gracious and accommodating. But she also seemed in a bit of a hurry. Note to Carrie: If you eliminate “like” from your vocabulary, think of the extra time you’ll have!

At some point in history, “like” burst onto the scene and refused to leave, much like karaoke. The difference is that karaoke eventually ENDS. A rendition of "Summer Nights" from Grease, sung by two fully-intoxicated women at a bar, is mercifully over after three minutes. Stories peppered with “like” seem to go on forever. If you don’t believe me, come to one of my daughter’s sleepovers, where you will be treated to dialogue like this:

“So I’m like sitting there and then she comes over and she’s like, ‘Emily, like are you going to ask him?’ And I’m like, ‘No way.’ So she’s like, ‘Oh, just do it. Like, maybe he’ll say yes.’ And I’m like, ‘You are so weird. Why would I like do that?’ And she’s like, ‘Because you’re like so that person.’ And I’m like, ‘I am not.’ And she’s like, ‘Okay, maybe you’re not like that person. But you’re definitely like THAT person.’”

The story resulted in gales of laughter and squeals from the girls. Moments after typing it on my PC, my spelling and punctuation tool exploded in frustration.

Being a history buff, I looked at some famous quotes and speeches over the years, hoping to see when "like" began popping up. I immediately eliminated the Revolutionary War era because nowhere did I ever read Patrick Henry boldly stating, “Like give me liberty or give me like death.”

Even during the Civil War, when our country split in two and couldn’t agree on ANYTHING, both sides were apparently united in their belief that “like” was not “liked” when it came to speech. Abraham Lincoln used the word exactly ZERO times in his Gettysburg Address, a fact quickly verified by the “find and replace” tool on my web browser. Frankly, I was surprised. After all, wasn’t the message of that speech about creating a unified nation? In other words, get along and LIKE each other! But Lincoln chose to use more eloquent prose and that’s probably a good thing. Somehow, the phrase, “Like four score and seven years ago, like our fathers brought forth on this continent, like a new nation, conceived in like Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are like created equal” doesn’t move me.

Fast forward nearly 100 years and still no sign of the word in our culture. When the Japanese rained bombs down on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt did not deliver the news by stating, “December 7, 1941. A day that will, like, live in infamy.”

I would have thought that "like" would have made its appearance in the late 1960s. After all, most of the country was high and unaware of what was coming out of their mouths, never mind what was going into same mouths. Yet I listened over and over to the audio feed of Neil Armstrong’s historic moon landing. Not once did I hear him say, “That’s like one small step for man, one like giant leap for mankind.”

Eventually I gave up, unable to find any historical quotes of significance peppered with “like.” Now I can’t even open a magazine without seeing the hated word in print numerous times. Journalists, in their attempts to quote subjects accurately and avoid being sued for libel, have apparently decided it’s best to include the word. A recent Rolling Stone interview with Leonardo DiCaprio netted the following quote:

“My mom always says I’m exaggerating and I’m like, ‘Mom, you are sorely mistaken.”

During a recent movie outing with my girls, we were treated to a trailer from Disney’s upcoming Tangled. Suddenly the following text flashed across the screen:

She’s been grounded like…forever.”

When I log onto Facebook, I'm immediately asked if I want to "like" everything from Chipotle’s restaurant to a sketch comedy revue called Pop Vulture. I LIKED it better when Facebook wanted to know if I was a “fan” of a particular page. Of course my daugher’s friends would have announced that they were “like fans of Justin Bieber.”

Is it possible to get away from "like?" Do the deaf use it in sign language? If so, I hope the sign is very simple – and painful. If there is indeed no sign for "like," might I suggest sticking an index finger into one’s eyeball? Perhaps that would keep deaf teenagers from using the word ad nauseum.

How can we stop the "like" epidemic? Whom do we ask? Certainly not our children, who would most likely reply, “Like huh?”

Desperate times call for desperate measures. In college I used to watch old Bob Newhart episodes with fraternity brothers and play a drinking game called “Hi Bob.” The rules were simple: Watch the show with a full beer in hand. Every time a character said, “Hi Bob,” or some form thereof, take a drink. It’s amazing how looped one can get during a 30-minute sitcom.

Maybe utterances of the word “like” should have similar consequences. Note I said similar since the prime offenders of “like overload” are not of legal drinking age, Carrie Underwood notwithstanding. But they could still face penalties. For every utterance of "like" that did not pertain to agreement or attraction, no iPod or iTunes for a week.

Somebody like alert Steve Jobs.

transitive verb

1 – to be suitable or agreeable to

2 – to feel attraction toward or take pleasure in

3 – every other word out of my daughter’s mouth

I love my kids. I truly do. I encourage communication with them. But despite the fact that they are my world and I heap affection on them at every moment, I hesitate to say that I “like” them. For, if I hear that word one more time, I’m like going to scream.

I am a stand-up comedian by trade. My profession relies on audience approval. Every time I walk on stage, I hope the audience will like me. But I don’t want them to “like, like me.”

Seriously, when did the word “like,” which has multiple meanings as evidenced by the above definitions taken directly from Merriam-Webster’s on-line dictionary, become the most overused and grating word in the English language?

Does anybody know? Perhaps I should ask country music superstar Carrie Underwood who, during a recent Today Show appearance, talked about like her marriage and like her upcoming tour and like her charity work and like the changes on American Idol. I have always liked Carrie Underwood, believing her music and her personality suitable for my kids. My oldest, now thirteen, even met her backstage before a concert and Carrie was exceptionally gracious and accommodating. But she also seemed in a bit of a hurry. Note to Carrie: If you eliminate “like” from your vocabulary, think of the extra time you’ll have!

At some point in history, “like” burst onto the scene and refused to leave, much like karaoke. The difference is that karaoke eventually ENDS. A rendition of "Summer Nights" from Grease, sung by two fully-intoxicated women at a bar, is mercifully over after three minutes. Stories peppered with “like” seem to go on forever. If you don’t believe me, come to one of my daughter’s sleepovers, where you will be treated to dialogue like this:

“So I’m like sitting there and then she comes over and she’s like, ‘Emily, like are you going to ask him?’ And I’m like, ‘No way.’ So she’s like, ‘Oh, just do it. Like, maybe he’ll say yes.’ And I’m like, ‘You are so weird. Why would I like do that?’ And she’s like, ‘Because you’re like so that person.’ And I’m like, ‘I am not.’ And she’s like, ‘Okay, maybe you’re not like that person. But you’re definitely like THAT person.’”

The story resulted in gales of laughter and squeals from the girls. Moments after typing it on my PC, my spelling and punctuation tool exploded in frustration.

Being a history buff, I looked at some famous quotes and speeches over the years, hoping to see when "like" began popping up. I immediately eliminated the Revolutionary War era because nowhere did I ever read Patrick Henry boldly stating, “Like give me liberty or give me like death.”

Even during the Civil War, when our country split in two and couldn’t agree on ANYTHING, both sides were apparently united in their belief that “like” was not “liked” when it came to speech. Abraham Lincoln used the word exactly ZERO times in his Gettysburg Address, a fact quickly verified by the “find and replace” tool on my web browser. Frankly, I was surprised. After all, wasn’t the message of that speech about creating a unified nation? In other words, get along and LIKE each other! But Lincoln chose to use more eloquent prose and that’s probably a good thing. Somehow, the phrase, “Like four score and seven years ago, like our fathers brought forth on this continent, like a new nation, conceived in like Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are like created equal” doesn’t move me.

Fast forward nearly 100 years and still no sign of the word in our culture. When the Japanese rained bombs down on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt did not deliver the news by stating, “December 7, 1941. A day that will, like, live in infamy.”

I would have thought that "like" would have made its appearance in the late 1960s. After all, most of the country was high and unaware of what was coming out of their mouths, never mind what was going into same mouths. Yet I listened over and over to the audio feed of Neil Armstrong’s historic moon landing. Not once did I hear him say, “That’s like one small step for man, one like giant leap for mankind.”

Eventually I gave up, unable to find any historical quotes of significance peppered with “like.” Now I can’t even open a magazine without seeing the hated word in print numerous times. Journalists, in their attempts to quote subjects accurately and avoid being sued for libel, have apparently decided it’s best to include the word. A recent Rolling Stone interview with Leonardo DiCaprio netted the following quote:

“My mom always says I’m exaggerating and I’m like, ‘Mom, you are sorely mistaken.”

During a recent movie outing with my girls, we were treated to a trailer from Disney’s upcoming Tangled. Suddenly the following text flashed across the screen:

She’s been grounded like…forever.”

When I log onto Facebook, I'm immediately asked if I want to "like" everything from Chipotle’s restaurant to a sketch comedy revue called Pop Vulture. I LIKED it better when Facebook wanted to know if I was a “fan” of a particular page. Of course my daugher’s friends would have announced that they were “like fans of Justin Bieber.”

Is it possible to get away from "like?" Do the deaf use it in sign language? If so, I hope the sign is very simple – and painful. If there is indeed no sign for "like," might I suggest sticking an index finger into one’s eyeball? Perhaps that would keep deaf teenagers from using the word ad nauseum.

How can we stop the "like" epidemic? Whom do we ask? Certainly not our children, who would most likely reply, “Like huh?”

Desperate times call for desperate measures. In college I used to watch old Bob Newhart episodes with fraternity brothers and play a drinking game called “Hi Bob.” The rules were simple: Watch the show with a full beer in hand. Every time a character said, “Hi Bob,” or some form thereof, take a drink. It’s amazing how looped one can get during a 30-minute sitcom.

Maybe utterances of the word “like” should have similar consequences. Note I said similar since the prime offenders of “like overload” are not of legal drinking age, Carrie Underwood notwithstanding. But they could still face penalties. For every utterance of "like" that did not pertain to agreement or attraction, no iPod or iTunes for a week.

Somebody like alert Steve Jobs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)